Blitzkrieg Definition

The noun blitzkrieg means a very quick, particularly violent and intimidating attack by one armed force against an enemy, but it almost always refers specifically to the German military offensive during World War II. Blitzkrieg in the Second World War was a German military offensive tactic of striking a specific target quickly with a strong concentration of forces, causing as much damage as possible.

Ju 87 Bs over Poland, September–October 1939In English and other languages, the term had been used since the 1920s. The term was first used in the publications of Ferdinand Otto Miksche, first in the magazine 'Army Quarterly' (according ), later as a book 'Blitzkrieg: The German Method 1939-1941', which might be the first use of the term in military circles in connection to German tactics. The British press used it to describe the German successes in Poland in September 1939, called by Harris 'a piece of journalistic sensationalism – a buzz-word with which to label the spectacular early successes of the Germans in the Second World War'. It was later applied to the bombing of Britain, particularly London, hence '.

The German popular press followed suit nine months later, after the fall of France in 1940; hence although the word had been used in German, it was first popularized by British journalism. Referred to it as a word coined by the Allies: 'as a result of the successes of our rapid campaigns our enemies. Coined the word Blitzkrieg'. After the German failure in the Soviet Union in 1941, use of the term began to be frowned upon in the Third Reich, and Hitler then denied ever using the term, saying in a speech in November 1941, 'I have never used the word Blitzkrieg, because it is a very silly word'. In early January 1942, Hitler dismissed it as 'Italian phraseology'. Military evolution, 1919–1939 Germany. The dive-bomber was used in blitzkrieg operations.was provided in the form of the.

They would support the focal point of attack from the air. German successes are closely related to the extent to which the German Luftwaffe was able to control the air war in early campaigns in Western and Central Europe, and the Soviet Union. However, the Luftwaffe was a broadly based force with no constricting central doctrine, other than its resources should be used generally to support national strategy. It was flexible and it was able to carry out both operational-tactical, and strategic bombing. Flexibility was the Luftwaffe 's strength in 1939–1941. Paradoxically, from that period onward it became its weakness.

While Allied Air Forces were tied to the support of the Army, the Luftwaffe deployed its resources in a more general, operational way. It switched from missions, to medium-range interdiction, to strategic strikes, to close support duties depending on the need of the ground forces. In fact, far from it being a specialist panzer spearhead arm, less than 15 percent of the Luftwaffe was intended for close support of the army in 1939. Limitations and countermeasures Environment The concepts associated with the term blitzkrieg—deep penetrations by armour, large encirclements, and combined arms attacks—were largely dependent upon terrain and weather conditions. Where the ability for rapid movement across 'tank country' was not possible, armoured penetrations often were avoided or resulted in failure.

Terrain would ideally be flat, firm, unobstructed by natural barriers or fortifications, and interspersed with roads and railways. If it were instead hilly, wooded, marshy, or urban, armour would be vulnerable to infantry in close-quarters combat and unable to break out at full speed. Additionally, units could be halted by mud ( along the Eastern Front regularly slowed both sides) or extreme snow. Operation Barbarossa helped confirm that armour effectiveness and the requisite aerial support were dependent on weather and terrain. It should however be noted that the disadvantages of terrain could be nullified if surprise was achieved over the enemy by an attack through areas considered natural obstacles, as occurred during the Battle of France when the German blitzkrieg-style attack went through the Ardennes.

Since the French thought the Ardennes unsuitable for massive troop movement, particularly for tanks, they were left with only light defences which were quickly overrun by the Wehrmacht. The Germans quickly advanced through the forest, knocking down the trees the French thought would impede this tactic. Air superiority. The, especially when armed with eight rockets, posed a threat to German armour and motor vehicles during the in 1944.The influence of air forces over forces on the ground changed significantly over the course of the Second World War. Early German successes were conducted when Allied aircraft could not make a significant impact on the battlefield. In May 1940, there was near parity in numbers of aircraft between the Luftwaffe and the Allies, but the Luftwaffe had been developed to support Germany's ground forces, had liaison officers with the mobile formations, and operated a higher number of sorties per aircraft. In addition, German air parity or superiority allowed the unencumbered movement of ground forces, their unhindered assembly into concentrated attack formations, aerial reconnaissance, aerial resupply of fast moving formations and close air support at the point of attack.

Over time you can choose to do more things manually like skilling or item-buying for the full MOBA experience.Unleash your titanEver wanted to take a huge fire dragon or a big rock golem into the battle? Heroes of soulcraft para pc. No problem - we will join a new player into the running game.Choose your heroSelect one of several heroes: play the melee dwarf 'furious axe' Grimnor, the range fighter 'loose cannon' Keely, the mage supporter 'flower princess' Dalia or many more.Easy to learnHeroes of SoulCraft makes it very easy to learn the basics within a minute.

The Allied air forces had no close air support aircraft, training or doctrine. The Allies flew 434 French and 160 British sorties a day but methods of attacking ground targets had yet to be developed; therefore Allied aircraft caused negligible damage. Against these 600 sorties the Luftwaffe on average flew 1,500 sorties a day. On May 13, Fliegerkorps VIII flew 1,000 sorties in support of the crossing of the Meuse. The following day the Allies made repeated attempts to destroy the German pontoon bridges, but German fighter aircraft, ground fire and Luftwaffe flak batteries with the panzer forces destroyed 56 percent of the attacking Allied aircraft while the bridges remained intact.Allied air superiority became a significant hindrance to German operations during the later years of the war. By June 1944 the Western Allies had complete control of the air over the battlefield and their fighter-bomber aircraft were very effective at attacking ground forces.

On D-Day the Allies flew 14,500 sorties over the battlefield area alone, not including sorties flown over north-western Europe. Against this on 6 June the Luftwaffe flew some 300 sorties. Though German fighter presence over Normandy increased over the next days and weeks, it never approached the numbers the Allies commanded. Fighter-bomber attacks on German formations made movement during daylight almost impossible.

Subsequently, shortages soon developed in food, fuel and ammunition, severely hampering the German defenders. German vehicle crews and even flak units experienced great difficulty moving during daylight. Indeed, the final German offensive operation in the west, was planned to take place during poor weather to minimize interference by Allied aircraft. Under these conditions it was difficult for German commanders to employ the 'armoured idea', if at all. Counter-tactics Blitzkrieg is vulnerable to an enemy that is robust enough to weather the shock of the attack and that does not panic at the idea of enemy formations in its rear area.

This is especially true if the attacking formation lacks the reserve to keep funnelling forces into the spearhead, or lacks the mobility to provide infantry, artillery and supplies into the attack. If the defender can hold the shoulders of the breach they will have the opportunity to counter-attack into the flank of the attacker, potentially cutting off the van as happened to in the Ardennes.During the Battle of France in 1940, the (Major-General Charles de Gaulle) and elements of the 1st Army Tank Brigade made probing attacks on the German flank, pushing into the rear of the advancing armoured columns at times. This may have been a reason for Hitler to call a halt to the German advance.

Those attacks combined with 's would become the major basis for responding to blitzkrieg attacks in the future:, permitting enemy or 'shoulders' of a penetration was essential to channelling the enemy attack, and artillery, properly employed at the shoulders, could take a heavy toll of attackers. While Allied forces in 1940 lacked the experience to successfully develop these strategies, resulting in France's capitulation with heavy losses, they characterised later Allied operations. At the the Red Army employed a combination of defence in great depth, extensive minefields, and tenacious defence of breakthrough shoulders. In this way they depleted German combat power even as German forces advanced. The reverse can be seen in the Russian summer offensive of 1944, which resulted in the destruction of Army Group Center. German attempts to weather the storm and fight out of encirclements failed due to the Russian ability to continue to feed armoured units into the attack, maintaining the mobility and strength of the offensive, arriving in force deep in the rear areas, faster than the Germans could regroup. Logistics Although effective in quick campaigns against Poland and France, mobile operations could not be sustained by Germany in later years.

Strategies based on manoeuvre have the inherent danger of the attacking force overextending its, and can be defeated by a determined foe who is willing and able to sacrifice territory for time in which to regroup and rearm, as the Soviets did on the Eastern Front (as opposed to, for example, the Dutch who had no territory to sacrifice). Tank and vehicle production was a constant problem for Germany; indeed, late in the war many panzer 'divisions' had no more than a few dozen tanks. As the end of the war approached, Germany also experienced critical shortages in and stocks as a result of Anglo-American and blockade. Although production of Luftwaffe fighter aircraft continued, they would be unable to fly for lack of fuel. What fuel there was went to panzer divisions, and even then they were not able to operate normally.

Of those tanks lost against the United States Army, nearly half of them were abandoned for lack of fuel. Military operations Spanish Civil War German volunteers first used armour in live field conditions during the of 1936. Armour commitment consisted of Panzer Battalion 88, a force built around three companies of tanks that functioned as a training cadre for Nationalists. The Luftwaffe deployed squadrons of, dive bombers and as the. Guderian said that the tank deployment was 'on too small a scale to allow accurate assessments to be made.' The true test of his 'armoured idea' would have to wait for the Second World War.

However, the Luftwaffe also provided volunteers to Spain to test both tactics and aircraft in combat, including the first combat use of the Stuka.During the war, the Condor Legion undertook the which had a tremendous psychological effect on the populations of Europe. The results were exaggerated, and the concluded that the 'city-busting' techniques were now a part of the German way in war. The targets of the German aircraft were actually the rail lines and bridges.

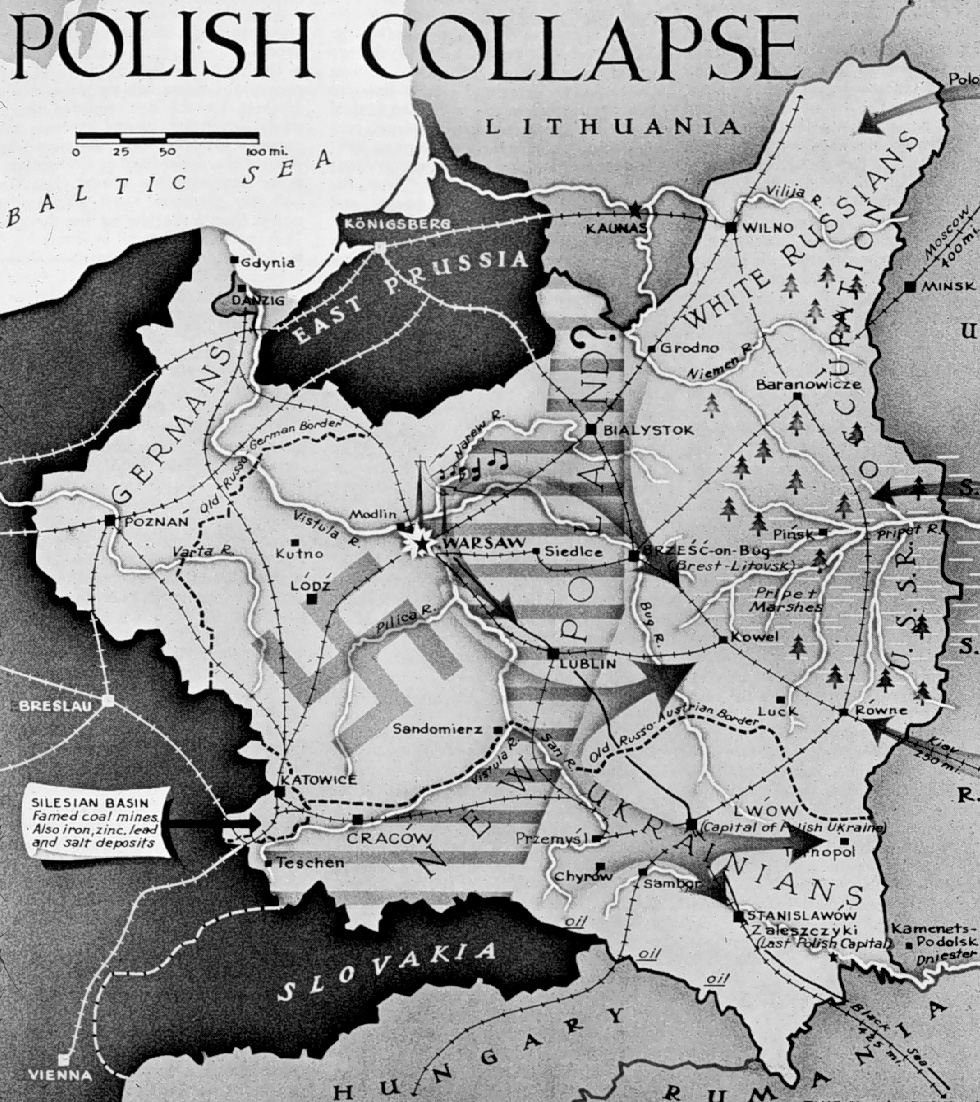

But lacking the ability to hit them with accuracy (only three or four saw action in Spain), a method of was chosen resulting in heavy civilian casualties. Poland, 1939. In Poland, fast moving armies encircled Polish forces (blue circles) but not by independent armoured operations. Combined tank, artillery, infantry and air forces were used.Despite the term blitzkrieg being coined by journalists during the Invasion of Poland of 1939, historians Matthew Cooper and J. Harris have written that German operations during it were consistent with traditional methods. The Wehrmacht strategy was more in line with a focus on envelopment to create pockets in broad-front annihilation. Panzer forces were dispersed among the three German concentrations with little emphasis on independent use, being used to create or destroy close pockets of and seize operational-depth terrain in support of the largely un-motorized infantry which followed.While early German tanks, Stuka dive-bombers and concentrated forces were used in the Polish campaign, the majority of the battle was conventional infantry and artillery warfare and most Luftwaffe action was independent of the ground campaign.

Matthew Cooper wrote thatthroughout the Polish Campaign, the employment of the mechanised units revealed the idea that they were intended solely to ease the advance and to support the activities of the infantry.Thus, any strategic exploitation of the armoured idea was still-born. The paralysis of command and the breakdown of morale were not made the ultimate aim of the. German ground and air forces, and were only incidental by-products of the traditional maneuvers of rapid encirclement and of the supporting activities of the flying artillery of the Luftwaffe, both of which had as their purpose the physical destruction of the enemy troops. Such was the Vernichtungsgedanke of the Polish campaign.John Ellis wrote that '.there is considerable justice in Matthew Cooper's assertion that the panzer divisions were not given the kind of strategic mission that was to characterize authentic armoured blitzkrieg, and were almost always closely subordinated to the various mass infantry armies.' Wrote, 'Whilst Western accounts of the September campaign have stressed the shock value of the panzer and Stuka attacks, they have tended to underestimate the punishing effect of German artillery on Polish units. Mobile and available in significant quantity, artillery shattered as many units as any other branch of the Wehrmacht.'

Low Countries and France, 1940. German advances during the Battle of BelgiumThe German invasion of France, with subsidiary attacks on Belgium and the Netherlands, consisted of two phases, Operation Yellow ( ) and Operation Red ( ). Yellow opened with a feint conducted against the Netherlands and Belgium by two armoured corps. Most of the German armoured forces were placed in Panzer Group von Kleist, which attacked through the, a lightly defended sector that the French planned to reinforce if need be, before the Germans could bring up heavy and siege artillery. There was no time for such a reinforcement to be sent, for the Germans did not wait for siege artillery but reached the Meuse and achieved a breakthrough at the in three days.The group raced to the, reaching the coast at Abbeville and cut off the BEF, the and some of the best-equipped divisions of the in northern France. Armoured and motorised units under Guderian, Rommel and others, advanced far beyond the marching and horse-drawn infantry divisions and far in excess of that with which Hitler and the German high command expected or wished. When the Allies counter-attacked at using the heavily armoured British and tanks, a brief panic was created in the German High Command.

The armoured and motorised forces were halted by Hitler outside the port of, which was being used to evacuate the Allied forces. Promised that the Luftwaffe would complete the destruction of the encircled armies but aerial operations failed to prevent the evacuation of the majority of the Allied troops. In some 330,000 French and British troops escaped.Case Yellow surprised everyone, overcoming the Allies' 4,000 armoured vehicles, many of which were better than German equivalents in armour and gun-power. The French and British frequently used their tanks in the dispersed role of infantry support rather than concentrating force at the point of attack, to create overwhelming firepower. German advances during the Battle of FranceThe French armies were much reduced in strength and the confidence of their commanders shaken.

With much of their own armour and heavy equipment lost in Northern France, they lacked the means to fight a mobile war. The Germans followed their initial success with Operation Red, a triple-pronged offensive. The XV Panzer Corps attacked towards, attacked east of Paris, towards and the XIX Panzer Corps encircled the Maginot Line. The French were hard pressed to organise any sort of counter-attack and were continually ordered to form new defensive lines and found that German forces had already by-passed them and moved on. An armoured counter-attack organised by Colonel de Gaulle could not be sustained and he had to retreat.Prior to the German offensive in May, Winston Churchill had said 'Thank God for the French Army'. That same French army collapsed after barely two months of fighting.

This was in shocking contrast to the four years of trench warfare they had engaged in during the First World War. The French president of the Ministerial Council, Reynaud, attributed the collapse in a speech on 21 May 1940:The truth is that our classic conception of the conduct of war has come up against a new conception.

At the basis of this.there is not only the massive use of heavy armoured divisions or cooperation between them and airplanes, but the creation of disorder in the enemy's rear by means of parachute raids.The Germans had not used paratroop attacks in France and only made one big drop in the Netherlands, to capture three bridges; some small glider-landings were conducted in Belgium to take bottle-necks on routes of advance before the arrival of the main force (the most renowned being the landing on in Belgium). Eastern Front, 1941–44., p. 14. ^, p. 6. ^, p. 22. ^, pp. 283–287. ^, pp. 337–338., p. 260., p. 54. ^, p. 4.

^, pp. 4–5. ^, ch. 29–31., p. 254., p. 34., pp. 329–330., pp. 4–5. ^, p. 7.

^, p. 109., pp. 334–336., pp. 31, 64–65., p. 345., p. 135. ^, p. 337. Sfn error: no target: CITEREFMiksche1941., pp. 338–339., pp. 336–338., p. 5., p. 1776., p. 173., pp. 30–31., p. 23., p. 37., p. 7., p. 30., p. 152., pp. 3–5., p. 101., pp. 17–18., p. 121., pp. 18–20, 22–24. ^, pp. 435–438., p. 191., p. 200.