Detective Story Dateline

Rasmussen shortly before her 1985 weddingDateFebruary 24, 1986 ( 1986-02-24)Location,:ConvictedStephanie LazarusChargesFirst-degree murderVerdictGuiltySentence27 years to lifeLitigationRasmussen v. City of Los Angeles, Rasmussen v. Lazarus,Francis v. City of Los AngelesOn February 24, 1986, the body of Sherri Rasmussen (born February 7, 1957 ) was found dead in the apartment she shared with her husband, John Ruetten, in, United States. She had been beaten and shot three times in a struggle. The (LAPD) initially considered the case a botched, and were unable to identify a suspect.Rasmussen's father believed that Stephanie Lazarus, an LAPD officer, was a.

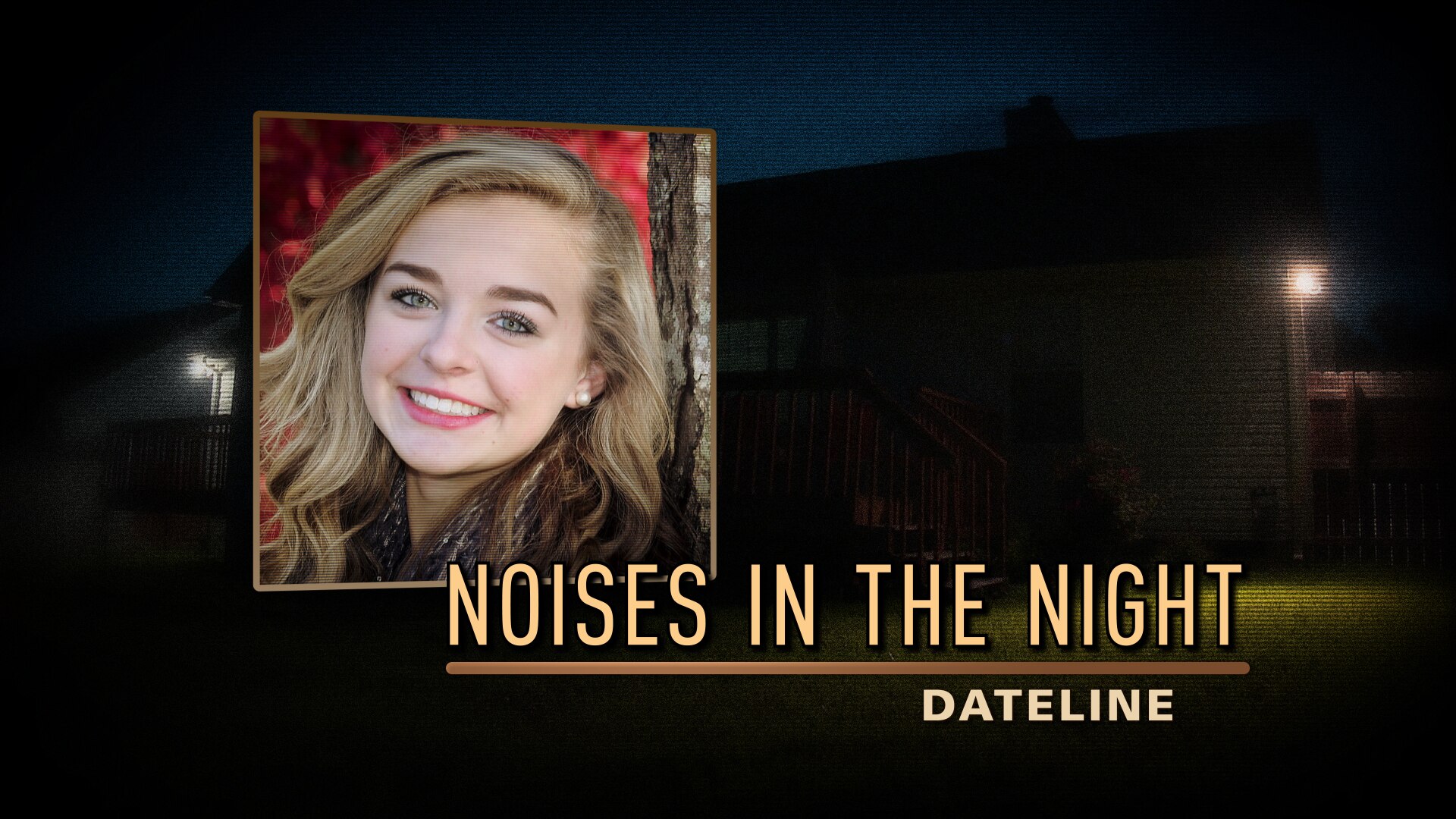

Listen to Dateline NBC episodes free, on demand. When Sherri Rasmussen is found murdered, police are convinced it’s a burglary gone wrong. The case remains unsolved for over two decades until another detective finds the key that unlocks the mystery of what actually happened to her. Josh Mankiewicz reports. Originally aired on NBC on November 22, 2019. 200 videos Play all Dateline Episode Trailers Dateline NBC Fayetteville’s Kelli Bordeaux case: Private investigator solves soldier’s disappearance - Duration: 34:01. True Crime Daily 2,285,059.

Detectives who re-examined the files in 2009 were eventually led to Lazarus, by then herself a detective. A sample she unknowingly discarded was matched to one from a bite on Rasmussen's body that had remained in the files. Lazarus was convicted of the murder in 2012 and is serving a sentence of 27 years to for at the in.Lazarus the conviction, claiming that the age of the case and the evidence denied her.

She also alleged that the was improperly granted, her statements in an interview prior to her arrest were compelled, and that evidence supporting the original should have been admitted at trial. In 2015, the guilty verdict was upheld by the.Some of the police files suggest that evidence that could have implicated Lazarus earlier in the investigation was later removed, perhaps by others in the LAPD. Rasmussen's parents unsuccessfully sued the department over this and other aspects of the investigation. Jennifer Francis, the who found key evidence from the bite mark, unsuccessfully sued the, claiming she was pressured by police to favor certain suspects in this and other high-profile cases and was retaliated against when she. Parker Center, where Lazarus was interrogated and arrestedA short time later, detectives from the RHD who had been selected for their lack of personal connection to Lazarus called her from the lockup at, the department's headquarters. Bratton had ordered that location be used since Lazarus would have to surrender her gun in order to enter it, limiting the possibility she might resist violently when she was arrested (immediately following the interview, as was the plan) or realized that she was the prime suspect. The detectives, Greg Stearns and Dan Jaramillo, told her they had someone in custody who wanted to talk about an art theft.After Lazarus had checked her gun and come to the interrogation room, they explained that this was really about some loose ends they were trying to tie up in the Rasmussen case, since her name had come up in the investigation.

They claimed they wanted a private setting because, while Ruetten was an old boyfriend, Lazarus had long been married to someone else and they did not want her private life to become the subject of. Stearns and Jaramillo knew they would have to tread carefully since Lazarus herself was well aware of police interview techniques and her rights to and legal counsel, which she could invoke at any time.They rambled and digressed from the subject at times, sometimes discussing unrelated police business, but eventually came back to Rasmussen. Lazarus claimed to recall little due to the intervening years, but gradually revealed more and more knowledge—including oblique acknowledgements of her visits to the Ruetten condo and a specific encounter at Rasmussen's office—until she accused her colleagues of considering her a suspect.

The detectives mentioned it was possible they had DNA evidence from the crime scene, and requested DNA samples from Lazarus. Lazarus declined and thereafter left the room. She was immediately arrested and charged with the murder.Once she had been arrested, the teams in Simi Valley began searching Lazarus' home and car. In her house they found her journal from the mid-1980s, with numerous mentions of her love for Ruetten and her despondence over his engagement to Rasmussen (and no mentions of her gun having been stolen). Her computer showed that she had searched the Internet for Ruetten's name on several occasions during the late 1990s.As the investigating detectives had been, many LAPD officers were stunned at the idea that Lazarus might have murdered someone.

Fellow detectives recalled her as vivacious and supportive (although some also recalled that her behavior when angry had led some to refer to her as 'Spazarus' behind her back). A case she had been developing from her art-theft work, with and real estate fraud aspects, had to be dropped since it was highly unlikely that it could be prosecuted successfully if the lead investigator herself were facing a murder charge.After her arrest, Lazarus was allowed to retire early from the LAPD; she was held in the. A hearing was not held for almost six months. Judge Robert J.

Perry surprised both sides when he set the amount at $10 million in cash, well above what the defense had suggested and more than twice what prosecutors had proposed. The case against Lazarus was very strong, he said, and thus, she might well be at risk to flee the country or obtain weapons through her husband.

Lazarus' lawyer, Mark Overland, said the judge did not understand the case well and contrasted the high figure with the $1 million set for and when they were charged with murder. Several months later, her brother claimed she was not receiving adequate treatment for an unspecified cancer while in custody, either. Pretrial defense motions In October, Overland moved to have the entire case dismissed on the grounds that the initial investigators should have identified Lazarus as a suspect but failed to do so. In support, he cited missing aspects of the original file such as recordings of interviews, Sherri Rasmussen's blood report, as well as a test Ruetten allegedly failed.

The motion noted Nels Rasmussen's belief that Lazarus was a suspect at the time of the murder, and his ensuing efforts to get the LAPD to take that theory seriously. Because of this failure, he argued, Lazarus' rights had been adversely affected since the quality of evidence had degraded in the intervening 23 years.Overland argued that of the required that the long delay in bringing charges which adversely affected the quality of the evidence which might otherwise have allowed him to make a better case that there were other suspects, or that the evidence against Lazarus was not as solid as the prosecution claimed, should be considered sufficiently negligent on the state's part to justify dismissing the case. For example, a witness who could have corroborated the prosecution's account of the confrontation between Rasmussen and Lazarus at the hospital had died in 2000. Prosecutors argued in response that Perry was required to apply federal standards, under which such a delay could only be considered prejudicial if it was shown to have been intentional. Perry agreed, and let the case proceed.Following that denial, Overland moved to the that had been executed on Lazarus' home, vehicle and spaces she utilized at work, and suppress the evidence obtained from them.

They were, he argued, based on stale information and did not sufficiently establish a nexus between the places searched and the likelihood of finding evidence there; Lazarus had not moved to her present residence, he observed, until 1994, eight years after the murder, and the in support of the warrant did not provide any reason why evidence might be found there. A bite, a bullet, a gun barrel and a broken heart. That's the evidence that will prove to you that defendant Stephanie Lazarus murdered Sherri Rasmussen.Deputy District Attorney Shannon PresbyThe trial began in early 2012.

In, prosecutors argued Lazarus' motive for the murder was jealousy over Sherri Rasmussen's relationship with Ruetten. In his opening argument, prosecutor Shannon Presby summed up the case as, 'A bite, a bullet, a gun barrel and a broken heart.

That's the evidence that will prove to you that defendant Stephanie Lazarus murdered Sherri Rasmussen.' A highlight of the case was Ruetten's testimony. Several times he became emotional and wept, particularly when recalling his courtship of Rasmussen. He allowed that having sex with Lazarus while he was engaged to his future wife was 'a mistake'.In cross-examining the police detectives and other technicians who had originally investigated the killing, Overland stressed the original botched burglary theory and pointed to evidence, such as the similar burglary that happened shortly thereafter, that he claimed supported it. He also highlighted evidence that was not analyzed, such as a bloody fingerprint on one of the walls, to suggest that other suspects had not been adequately excluded from consideration. He questioned whether it could be truly inferred from the weapon used that it was Lazarus' lost gun, since.38s were in wide use. Since the DNA from the bite mark was central to the prosecution's case, he attacked it vigorously, pointing to improper storage procedures and a hole the tube had left in an envelope that he said would have allowed Lazarus' DNA to be added to it long after it had been collected.During the two days in which he presented his case-in-chief, Overland focused on the prosecution's theme of a Lazarus, presenting friends of hers who denied that she was showing any signs of violence or despondence over her failed relationship with Ruetten at the time of the murder.

Excerpts from a contemporaneous journal were offered as evidence; Lazarus wrote in it of dating several different men, none of them Ruetten. He reinforced his attack on the, calling as his last witness a fingerprint expert who said that some prints at the crime scene did not match those of Lazarus.Both prosecution and defense reiterated their themes in. After showing the jury of eight women and four men photographs of a beaten, bloodied Rasmussen, prosecutor Paul Nunez told them, 'It wasn't a fair fight. This was prey caught in a cage with a predator.'

Overland dismissed the entire case as 'fluff and fill,' save for the 'compromised' bite-mark DNA sample. He moved for a after Nunez reminded the jurors that no had been provided for the time of the murder, since defendants' refusal to testify cannot be held against them, but Perry denied it, saying he did not take that as directly suggesting Lazarus herself had refused to testify and thus her right against had not been violated.In March, after several days of, Lazarus (then 52) was convicted of first-degree murder. Later that month, she was sentenced to 27 years to, and she is currently serving her sentence at the in.

After credit for time served before the trial, she will be eligible for parole in 2034. Litigation alleging police malfeasance As evidence was introduced at the trial, it became apparent that not all the evidence available and in possession of the LAPD had been found. Recordings and transcripts of interviews with both Nels Rasmussen and Ruetten that discussed Lazarus were absent from the file, although both remembered them when called to testify, and other aspects of the missing interviews are alluded to in other interviews in the file. The only mention of Lazarus during the initial investigation is a brief note of Mayer's in which he reports that Ruetten had confirmed that she was a 'former girlfriend.'

Two lawsuits have been filed based on these allegations. One, by Nels and Loretta Rasmussen, has been dismissed as time-barred. The other, a suit by criminalist Jennifer Francis (Butterworth at the time she tested what turned out to be Lazarus' DNA on the bite mark), ended with a judgment in the city's favor.

It alleged misconduct in not only the Rasmussen case but other high-profile investigations, and that she and others suffered retaliation and harassment from superiors when they tried to report this and accurately report the results they had found. Rasmussens Records also showed that, in 1992, shortly after Nels Rasmussen had offered to pay for DNA analysis on the remaining forensic evidence from the case, all samples other than the bite swab that might have helped to identify an attacker had been checked out of the coroner's office by a detective named Phil Morrill. While this appeared to have been part of the routine transfer of records to the LAPD, the evidence could not be located in department files, suggesting the samples were intentionally lost.

Only the bite swab, inadvertently left behind at the coroner's office, remained to connect Lazarus to the crime.In 2010, the Rasmussens filed a civil lawsuit against the city, the LAPD, Ruetten (named only as an without any specific claims), Lazarus and 100. They alleged that the coverup, including the act of allowing Lazarus to periodically review the case file, and the LAPD's hostility towards them, starting on the night after the murder and continuing when they pressed the Lazarus claim throughout the 1990s amounted to a violation of their civil rights,. They further alleged against Lazarus and the Does.Since the civil-rights claim included a violation of, the city successfully petitioned for to federal court.

After the Rasmussens to dropping the federal claim with, waiving the right to any further legal action against the city at that level, they were allowed to refile an amended claim in state court, and did so in 2011. There, the city was found to be from liability for all of the claims except the civil rights violation. When the Rasmussens filed an amended complaint consisting of just that, the judge dismissed it because he believed it was barred by their earlier stipulation in federal court.The Rasmussens appealed.

In its response, the city raised the as a defense, something it had not done when the suit was originally filed. The upheld the suit's dismissal on those grounds, that the Rasmussens' time to sue was limited once they broke off contact with the LAPD in 1998; the last year they could thus have filed suit was 2000.

The declined to hear the case in March 2013. Jennifer Francis Francis filed her suit late in 2013, following the rejection of her claim by the city and a finding by the state's that she had a right to sue. She alleges that after finding that the DNA from the bite belonged to a woman, the LAPD detective supervising her verbally steered her away from Lazarus as a suspect, without naming her. When Nuttall called her and told her the Van Nuys detectives were working the and had identified Lazarus as a suspect, she did not share what her supervisor had told her for fear of retaliation.According to Francis, the Rasmussen case was not the only one in which she believed DNA evidence was being purposefully ignored by the department. She was told 'We're not going there' in one case where she suggested comparing a partial profile from one victim with that of a suspect in a string of similar unsolved murders, also from the 1980s.

Work she did on the DNA found on Jill Barcomb, believed to have been killed by the, revealed instead that she was a victim of, another active around the same time in the Los Angeles area; he was ultimately convicted and sentenced to death in 2010. After she suggested doing DNA analyses of found on two teenage girls also believed to be victims of the Hillside Strangler, another detective discouraged her with the words, 'We don't want to open that can of worms.' A short time later she learned the semen samples had been destroyed; she could not find out why.At the end of 2009, while prosecutors were preparing for the in the Lazarus trial, she met with an assistant D.A. And told her about the resistance she had initially encountered over the possibility of Lazarus as a suspect in the Rasmussen murder. Several months later she was called into her supervisor's office and asked to relate those events.

A month later she told Detective Nuttall, who had spearheaded the reinvestigation that led to Lazarus' arrest, as well.The next month she was called into her supervisor's supervisor's office, and told to go to an employee counseling service, an act she knew to be punitive, 'because you look stressed.' The therapist who spoke with her seemed to Francis to be more interested in finding out what she knew about the Lazarus case and who she might have shared it with. After two sessions in which she declined to share that information, she was again called into her supervisor's office and told she was not cooperating and needed to 'talk this out.' She told the therapist she was getting a lawyer, after which further sessions were canceled as a 'mistake.'

Two detectives from RHD interrogated her the next month, July 2010. She told them she was concerned that events leading to Lazarus's arrest in which she was involved had been portrayed differently in the media than she recalled them, putting the department in a more favorable light. Nuttall as well, she recalled, had been placed in an equally difficult position, since he told her that Lazarus may have learned that they had reopened the investigation despite the precautions he and Barba had taken.In the wake of these events, Francis claims, she was taken off the upcoming case despite the work she had done on it, including the DNA sample that had led the police to their suspect. The same detective who had insisted Lazarus was not involved in the Rasmussen killing, she noted, had played a major role in investigating the Sleeper. In another meeting, her supervisor threatened her with more counseling and told her she was 'obsessed. Emotional' and 'shouldn't have said anything.' She was transferred to a non-analytical position.The retaliation continued after Lazarus was convicted, Francis claimed.

She faced more retaliatory action from her supervisors, whom she also accused of other female criminalists, and was again transferred. A report from the department's on her complaint to was delayed and appeared to have been reviewed by someone else prior to her receipt of it.In 2015, the parties made motions to the judge as to what evidence could be heard by a jury at trial. At the beginning of 2017, Superior Court Judge Michael Johnson ruled that Francis could proceed to trial alleging a violation of state labor law. He found there were no triable issues of fact on her claims of harassment, discrimination and retaliation. In April 2019, a jury found for the city. Appeal Lazarus filed a lengthy appeal of her conviction in May 2013 with the, Second District, Division Four, which has over 's courts.

Her attorney, Donald Tickle of, argued that Perry had erred in his rulings for the prosecution on all four pretrial motions Overland had filed. Tickle argued that multiple supported the defense arguments over those of the prosecution, and sometimes directly contradicted them. For example, he argued, Perry had applied the to the detectives' reliance on an admittedly defective search warrant based on the fact that the judge had issued the warrant after reviewing the affidavit. But Tickle pointed to an existing California case, which had expressly held that the state cannot rely purely on the warrant's issuance by a judge to establish sufficient good faith that.Tickle also attacked Perry's rulings limiting the defense's ability to put on evidence suggesting the initial botched burglary theory of the crime was more credible than the prosecution claimed. The prosecution had not moved to exclude third-party culpability evidence despite claiming the initial investigation's conclusion was erroneous during its, which led Perry to ask if they were conceding that it was. Nevertheless, he told Overland that without 'some remarkable similarities' between the burglary that killed Rasmussen and the one that happened nearby later he would not allow the defense to explore the later burglary, since there were also important dissimilarities.Perry, Tickle said, had misread the primary California case Overland had relied on as not applying to evidence of third-party culpability, while other cases made clear the statute it interpreted did indeed cover that. That case also imposed a lower standard of admission than 'remarkable similarities'.

You managed to survive after the zombie apocalypse and now you have to struggle to keep living fighting with zombies, helping scientists gather information about the disease in order to develop an antivirus.First person shooter for survival.Dead Bunker 4 Apocalypse — is a first-person shooter with its history, missions and shooting zombies that captured the world. Your main goal is to find the documents that will help develop an antivirus. Zombie apocalypse 2 game. Explore the world, get new weapons, save other survivors.

The use of a.38 caliber weapon and a similar residence in both burglaries established a strong possibility of a common for both crimes, Tickle said.As a result of this ruling, Overland had been denied the opportunity to Mark Safarik, the last prosecution witness and an FBI expert on burglaries, who had testified that the crime scene suggested a staged burglary, as opposed to a real one that had been interrupted in progress. Since the prosecution had told the court at a prior to Safarik's testimony that they intended to limit their questioning to supporting this theory, Perry similarly limited the defense on cross. However, Tickle argued, since Safarik's own report had considered the other burglary, testimony about that should have been allowed. Decision A panel of three judges—, Thomas Willhite Jr. And —heard in the case in June 2015.

A month later they reached their decision, unanimously upholding Lazarus' conviction.The court's primary was that Lazarus and her attorneys had failed to establish that Perry's rulings resulted in any to her ability to mount an effective defense. The warning, derived from the U.S.

Supreme Court's holding in that government employees whose terms of employment require them to cooperate with internal investigations retain their rights against compelled but can still be disciplined by their employers for their refusal to cooperate, balances the state's interest in conducting thorough investigations of possible employee misconduct with the constitutional rights of the employees under investigation. The Frye standard is a to determine whether a particular technology used to obtain evidence is reliable enough to admit that evidence. It was established by Frye v. United States, a 1923 case where the prosecution sought to introduce evidence that the defendants' rose when he denied participation in a murder, suggesting he was being untruthful; the federal appeals court affirmed a lower-court ruling that that test had not yet gained enough supporting consensus among scientists to be admissible.

January 28, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

Associated Press. March 8, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

Retrieved July 28, 2015. (PDF). November 21, 2013. Archived from (PDF) on January 3, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2013. ^ Jackson, Hillary (July 13, 1985). Retrieved December 21, 2015.

^ Elias, Paul (February 24, 2013). Retrieved November 25, 2013. ^. October 30, 2013.

Retrieved December 14, 2013. ^ Mikulan, Stephen (September 1, 2012). Archived from on December 3, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2013. ^ McGough, Matthew (June 2011).

Retrieved November 25, 2013. Pelisek, Christine (March 8, 2012).

Retrieved January 5, 2020. ^ (July 2012).

Retrieved November 25, 2013. ^ Deutsch, Linda (February 15, 2012). Archived from on December 9, 2013.

Retrieved November 28, 2013. ^ Blankstein, Andrew; Rubin, Joel (June 10, 2009). Retrieved November 30, 2013. ^ Romano, Tricia. Archived from on October 17, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

^, 2015-09-10 at the, Second Appellate District, Division Four; July 13, 2015; p. Lazarus, 14–15.

^ Kandel, Jason (March 8, 2012). Retrieved March 3, 2019. People v. Lazarus, 10. Rubin, Joel; Blankstein, Andrew (June 13, 2009). Retrieved December 1, 2013. People v.

Lazarus, 12–13. Rubin, Joel (December 19, 2009). Retrieved November 20, 2013.

Rubin, Joel; Andrew, Blankstein (March 12, 2010). Retrieved December 12, 2013. Blankstein, Andrew; Rubin, Joel (October 20, 2009). Retrieved December 14, 2013. Lazarus Appeal, 58–73. ^ Lazarus Appeal, 73–103.

Lazarus Appeal, 103–110., (1967). Lazarus Appeal, 110–128., 1913 ( 1923)., (1994).

Chang, Wendy; Ufkes, Frederick (January 2013). Lazarus Appeal, 128–153. Breuer, Howard; Keating, Caitlin; Hanlon, Greg (December 4, 2017). Retrieved January 30, 2018.

^ (February 29, 2012). Archived from on December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2013. Gray, Madison (February 8, 2012). Retrieved September 15, 2012. Deutsch, Linda (March 5, 2012).

Archived from on March 9, 2012. Retrieved December 13, 2013. Lavietes, Bryan (May 11, 2012).

Archived from on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 15, 2012. ^ Tchekmedyian, Alene (April 5, 2019). Retrieved May 21, 2019. ^.

November 15, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2013. March 30, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2013. September 8, 2015. Archived from on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

^ Tickle, Donald (May 28, 2013). Archived from (PDF) on January 3, 2019.

Retrieved January 2, 2019. Lazarus Appeal, 70–73., (1988) 204 Cal.App.3d 1208.

^ Lazarus Appeal, 155–180. (2011), 52 Cal.4th 452. ^ People v. Lazarus, 24–29. People v. Lazarus, 30–38. People v.

Lazarus, 38–40. People v. Lazarus, 40–42. ^ People v. Lazarus, 46–54. People v.

Lazarus, 62–67. People v. Lazarus, 68–71. People v. Lazarus, 73–75External links. – – 14 January 2017.